Kanchenjungha is an enigmatic film that deals with a day in the life of an upper middle class family holidaying in Darjeeling. On the surface it is about family dynamics but at another level is a deep look at relationships. Each person in the family circle of Raibahadur Indranath Choudhary (Chhobi Biswas) is seeking something. Indranath rules his family with an iron fist, and wants his daughter Monisha (Alkananda Roy) to marry the upwardly mobile Mr. Bannerjee (N. Vishwanathan) just as he persuaded his older daughter Anima (Anubha Gupta) to marry the affluent Shankar (Haridhan Mukherjee). His wife Lavanya (Karuna Bannerjee) is ruled by his wishes and unable to speak her mind. The entourage is rounded out by Lavanya’s brother Jagadish Chatterjee (Pahari Sanyal) whose only wish it is to spot the rare bird he keeps hearing sing in the trees, and Indranath’s son played by Anil Chatterjee, whose desires to hook up quickly with some westernized woman in the tourist haven. We see Anima surreptitiously hiding a letter, while her husband Shankar is quite vocal about the ills of marriage without love when he talks to Monisha. Anima and Shankar have a child who is shown reciting nursery rhymes as she is riding round and round the streets of Darjeeling on a horse. The wildcard in the pack shows up in the from of Ashok (Arun Mukherjee), a “commoner" who is not westernized, has read Tagore instead of English Literature, and is hoping that Indranath will give him a job.

The narrative is non-linear as we move from group one to group two to group three and so on, and then back again to group one. The groups themselves dissolve and reform in a constant series of interactions that take place in real time, and there is no story that is told in the film. All we see on the surface is a group of people, and their inner desires and aspirations are slowly exposed though interactions and conversations.

The uncle character, played by Pahari Sanyal, begins as an inconsequential birdwatcher but turns into a catalyst for change as he interacts in turn with his sister, then Monisha, and then Ashok. Anima and Shankar have a chasm of differences between them, and one common goal of happiness for their daughter. To achieve this Anima has to give up her clandestine affair while Shankar has to give up his habits of drinking, and gambling. The son is a sort of buffoonish character but even he gets to hang out with yet another westernized girl and her dog! Indranath’s wife Lavanya gives up her easy though servile attitude as she wishes to save the second daughter from the fate of the first. Monisha is braver than her elder sister and will say no to Banerjee as she does not care for him. In his turn, Banerjee realizes that his past liaisons mean nothing and it is Monisha he wants, so he gives up his pride and asks her to let him know if she changes her mind. Thus this film moves far away from the traditional Pather Panchali mode as characters exhibit modern mores and attitudes. Until these situations are resolved the little girl is seen going round and round on her horse, representing people trapped in circumstances. The one person who gives up nothing and stays inflexible till the end is Indranath. But in the end he is completely undermined, and Ray judges a closed mind that is at fault. Indranath has in essence turned his back to those very things that he wants – the mist has lifted for all, the peak is shining through, but Indranath is walking away from it!!!

In a 1984 interview with Satyajit Ray, directed by Shyam Benegal and filmed by Govind Nihalani, Ray mentions that he has adapted the works of Bibhutibhushan Bandopadhyay (Apu trilogy), Rabindranath Tagore, and several modern writers, but when he writes a film (like Nayak and Kanchenjunga) he likes to write about subjects and characters he is personally familiar with. In Kanchnejunga he deals with the middle class. “I couldn’t write about workers in a factory. But I’d like to make a film about workers in a factory. For that I need material, I need a story, which I haven’t found yet!” Having spent many a summer in Darjeeling, and being of the middle class himself, that milieu and their morals and behavioral norms were most familiar to him.

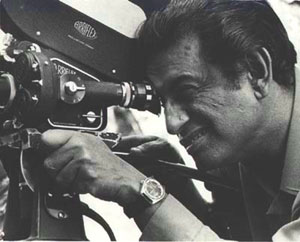

By the time of Kanchenjungha, Ray was the one running the camera as he needed to see the scene through the lens! In this film he makes excellent use of the billowing mists and the circuitous paths that people walk on as they meet and part, to show confusion and finally when things begin to get resolved the mists slowly lift and the setting sun sets the mountain peaks glowing. He uses an ensemble of characters and interactions between them to bring out the individuality of each character, and rather than making the film a story about one person, it becomes an oblique look at the upper middle class and their changing values, an indictment of the old attitudes and a celebration of the new social order. The cast is excellent

READ MORE HERE